Diocese of Hallam – Lenten Talks 2016 THE PASSION OF THE LORD

1.Preparing for the PassionRaymond E Brown, the great Scripture scholar, and author of a magisterial two volume work on the Passion narratives (“The Death of the Messiah”) once remarked that he had seldom heard a homily on the 'Our Father'. This is not very surprising as we never hear Matthew's 'Our Father' in the Sunday cycle of readings (though we do hear Luke's shorter, but perhaps more ancient, version on the 17th Sunday of Year C). If the lectionary does not give us the text the preacher is unlikely to preach it. In a sense the same might be said for the Passion Narratives. We do hear them proclaimed, and, in the case of John, sometimes dramatized. Each year on Passion (Palm) Sunday we hear the Passion of the appropriate year; and every Good Friday we listen to (and perhaps watch) the Passion according to John. But are they preached? We have the triumphal entry to recall as Holy Week begins, and the Passion is long. How many preachers will do more than make a few salient points regarding that Passion story? How many will pass it over in silence? Most preachers, I hope, say something about John's Passion but rarely, I suspect, is there the comparison made between John and the Passion heard a few days earlier; an exercise in biblical criticism the Church is surely encouraging. Seldom is the background filled in; or the details analysed, or the meaning probed.

Most people, despite forty years of the three year cycle of Sunday readings, would have difficulty distinguishing between details of the Gospel accounts and be able to identify by name stories or incidents found in only one of the Gospels. Let us test this theory:

In which Gospel do we hear Mary proclaim her 'Magnificat'?

In which Gospel do the Magi appear?

In which Gospel is Jesus announced to be 'The Lamb of God'?

In which Gospel is Lazarus raised from the dead?

In which Gospel does Jesus tell the story of the Good Samaritan?

In which Gospel does Veronica ('true icon') wipe the face of Jesus?

More theologically:

In which Gospel do the disciples have the hardest time, coming across as wholly useless, constantly failing 'to get it'?

Whose Gospel is the Gospel of mercy and compassion?

Which Gospel has been regarded as the great Teaching Gospel?

And finally, in which Gospel, or Gospels, does Jesus endure 'an agony in the Garden of Gethsemane'?

If asked to give an account of the Passion of Jesus most people would give a continuous narrative which would incorporate incidents from each of the Gospels. We would have a logically ordered plot, as we have a necessary order to events in the Passion – Jesus must be arrested before he is tried, and tried before he is condemned, and condemned before he is crucified, and hung on the cross before he dies and dead before he is buried. But some accounts would include the good thief (Luke) and the spear in the side (John); and Mary and John at the foot of the cross (John, although neither character is named; she is 'The Mother ' and 'Woman' and he is 'the Disciple Jesus loved').

Thus the nuances of each individual approach and thus the core message each evangelist is proclaiming is missed. To remedy this, and to hear of each evangelist's particular interpretation of the central act of salvation is our purpose. Thank you for joining me.

It is unlikely that you will all be able to hear all the talks, though delightful if you could. Each Saturday talk is repeated at a different venue on the following Wednesday evening. And each of the talks will appear on the Diocesan website (Adult education link) and on St Bede's website, soon after the repeated talk. A Bibliography will also be there, and paper copies are available here today. Questions are welcome but I don't want to delay too much so clarifications will be dealt with but anything which moves us away from what is strictly relevant I will put aside for the time being but if you can put the question in writing I will deal with it through the website.

Today we are seeing how each evangelist prepares us for the Passion and death of Jesus in the Gospel before Jesus arrives for the final time in Jerusalem. We will spend more time with Mark than with Matthew and Luke as they both use Mark as a source and we do not need to repeat what I will have said about Mark; and then we need to give a fair amount of time to John whose approach is so startlingly and gloriously different from that of the other three.“

The Synoptic Gospels are passion stories with long introductions”. So wrote the German scholar Martin Kahler though the quotation is often repeated as applying just to Mark. As we will see it applies to all the four canonical Gospels although the fourth Gospel has its own perspective on the way Jesus goes to his death, all prepare the reader/listener from the outset for Jesus destiny on a hill outside Jerusalem

.How each evangelist goes about that preparation is the topic of this first Lenten talk. Subsequently we will look at the Passionstories in each Gospel. Beginning with Mark, whose account Matthew closely follows but with curious additions which we will examine in talk 3. Luke is the topic of Talk 4. He modifies Mark in his gentle style, emphasising how Jesus heals and reconciles as he goes to his death. In talk 5 we look at the Passion in John's Gospel. John sees the same grim torture being carried out but he sees it all evoke the glory of God as Christ walks unbowed to his exaltation. Finally we will try and make sense of the story, and ask why it had to be this way. All the talks will be available for review on the adult education link to the website of the Diocese and the St Bede's Parish website.I will be following the majority scholarly view that Mark was the first Gospel to be completed, and Matthew and Luke used Mark as a main source though bringing in additional material of their own, ('M' and 'L', and some of which they may have had as a common source known to each of them (“Q”).

So we have much to do. Let's start looking at Mark's Gospel and the way the evangelist prepares us for Jesus suffering and death.

The structure of the Gospel is revealed in the opening sentence which gives the title of the work ”The beginning of the Good News of Jesus, Christ, Son of God.

”The name Jesus (=Joshua = Yehoshua) is a common personal name. According to Bauckham {“Eyewitnesses”, p.79} it was the sixth most popular male name in Palestine at this time. It means 'God saves'. 'Christ' is the English for Christus (Latin) or Christos (Greek) which translated the Aramaic mesiha (Heb: masiah) and means the anointed one. It was the title for one of the (many) heavenly beings who would inaugurate the endtime in some way and bring God's righteousness to the world ie Israel would be topnation again. Jesus is given the title only once in the Gospel (though he accepts the title when asked by the High Priest at his trial “Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?” [14,61]). At about the halfway stage, in the region of CaesareaPhillipi, Jesus asks the disciples “Who do people say I am?” and then “Who do you say I am?”. Peter replies, “You are the Christ” and is told to be silent about it. “Tell no one”. The Christ was to be a bringer of joy; but Jesus immediately announces, for the first time of three, that he will suffer and die. Peter remonstrates with him and is told, “Get behind me, Satan!” This Christ/Messiah will be a suffering Messiah/Christ; completely different to expectations. Yet this will be 'Good News'.

The title 'Son of God' (missing from some ancient manuscripts) is given to Jesus bydemons as he exorcises them (for they have supernatural knowledge). Otherwise it is heard only once as an affirmation. . When Jesus is dead the centurion who has seen how he died says, “Truly, this was the Son of God”. He is the only human being to make this affirmation in the Gospel; and it is when Jesus has died.

So the title, 'Christ' neatly divides the Gospel into too halves; and the title 'Son of God' forms an inclusio /brackets, a literary technique of which Mark is particularly fond

.The other phrase in the opening line /title is 'The beginning of the Good News'. “The whole of the Gospel is 'the beginning', so perhaps we should not be surprised by its ending which might be '...' when the women leave the tomb and say nothing to anyone “for they were afraid...” . Yet here we are carrying on the proclamation nearly two thousand years later. All the Gospels begin by taking us back to beginnings: Matthew “The genealogy of...”; Luke evokes Abraham and Sarah with his aged and pious and barren couple Zechariah and Elizabeth; and John goes back further than any of them to “In the beginning...”.

“Good News” (Gk: euangelion). Those who are biblically literate, as Mark expects his audience to be, would immediately think of Isaiah and the Good News that he announced. In the context of the (socalled) 'Songs of the Suffering servant' we hear, “How lovely on the mountains are the feet of him who brings Good News”. What was this 'Good News'?

The second (of three) part of the Book of Isaiah (DeuteroIsaiah: chapters 4055) was written in the time of the Exile in Babylon. Jerusalem had been looted and razed by the Babylonians under Nebuchadrezzar, the Temple destroyed and the elite – royalty, priests, scribes; and the skilled workers had been taken to Babylon and set to work there for their masters. Around this time the Pentateuch is completed; and the words of the prophets polished for publication; and the history books given something close to their final form. Ezekiel dates from this period as does DeuteroIsaiah. He announces a return to Jerusalem /Zion from captivity. So the hills will be laid low and the valleys filled in to make a superhighway for God's great cavalcade to sweep back to God's holy place.

The exile lasted a generation. Then King Cyrus of Persia allowed the exiles to return and the Temple rebuilt and the walls of the city repaired. This would be the work of Zerubbabel and Ezra the scribe and Nehemiah. But a generation is long enough for people to settle and put down roots (as Jeremiah had commanded them to do). A new generation does not have the same affection for 'the old place' as the exiles have. They know only one home and do not want to trek through the desert to – who knowswhat. And few did. It was not a divine cavalcade that swept down a super highway, but a motley series of groups who returned. And they came back to awasteland; and a people who they did not trust because they had not gone into exile (the peopleoftheland) and who did not trust them ('foreigners') and who thought that they had maintained the faith and the land which the exiles had abandoned. It was a difficult time for all. While the Temple was rebuilt it did not have the glory of the previous Temple of Solomon, nor the grandeur of the later Temple of Herod. In a sense God had not returned to Zion. The fulfilment of Isaiah's prophecy was still awaited.

Now, says Mark, God is coming to his city. A voice cries in the wilderness, 'Make a straight path for the Lord'. This quotation comes from the same part of Isaiah in which we hear of 'the Good News'. And 'the way' will be an important motif of Mark through the Gospel.

John appears as a new Elijah, the one to announce the coming Messiah; and 'immediately' (Mark's favourite word) Jesus of Nazareth is there and being baptised. Mark is the only evangelist who shows no embarrassment that Jesus is baptised by John (with a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins). Part of the reason for that lack of embarrassment is down to Mark's understanding of the meaning of the baptism. Later the sons of Thunder will ask if they can drink the cup that Jesus must drink and be baptised with the baptism with which Jesus must be baptised. In other words can they suffer and die as he must? For Mark baptism stands in parallel to death on the cross. It forms another inclusio that Mark likes so much.

At the baptism the heavens are ripped apart, a violent expression and the same one used for the ripping of the curtain of the Temple 'from top to bottom'. The voice from heaven calls Jesus 'My beloved son'. At Jesus death the centurion will say, “Truly, this was the son of God'.

The embarrassment of the other evangelists is easy to see: Matthew has John the Baptist say, “You should be baptising me”; Luke has John in prison already when the baptism takes place! The fourth evangelist does not describe the baptism but has the Baptist say what he saw at the baptism. The reasons for the embarrassment are also easy to see. Jesus has come from Nazareth to the Jordan at the call of John. He submits to John's baptism; so who is the greater? The baptism is a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. Is Jesus sinless or not? The historical truth of Jesus baptism by John in the Jordan cannot be doubted. It was a serious embarrassment but could not be airbrushed from the story. It was too much part of the story (cf Acts 1,22).

Why then does Mark show no embarrassment? The baptism shows Jesus purpose. This is why he came. Imagine the river Jordan after all these people ('the whole of Jerusalem') have been dunked by John and they have come up clean, leaving their sins behind. Then the one who is clean steps into the river made dirty and scummy bythe sins of the many. He comes out – dirty; bearing our sins. That was Mark's insight, which the other evangelists seem to have missed.

Immediately (again) after the baptism Jesus is driven into the wilderness by the Holy Spirit (which has come down on him at the baptism in the form of a dove). 'Driven' is another key word. It is used in the Book of Leviticus when the rituals of the Day of Atonement are described. This was the day when the sins of the High Priest and the people were atoned for. All the sins of the past year were wiped out by the proper conducting of the sacred rites. Two goats were chosen. The High Priest lay his hands on the head of one goat and that goat was 'driven away' in to the wilderness 'for Aziel', which seems to mean to its destruction. The other goat was slaughtered and its blood taken through the veil of the Temple by the High Priest and sprinkled on the Mercy Seat, God's footstool. This was the only time anyone entered the Most Holy Space. Here at the start of Jesus' ministry he is the goat who bears the sins of the people; at the end of his ministry he will be the goat whose blood is poured out. A fascinating inclusion. Jesus is the one who bears our sins; and who pays the price (cf Mk 10,45).

Mark describes the temptations very briefly. It is though a cosmic battle in the wilderness between good and evil. The conclusion 'the angels ministered to him'. It was a bruising encounter but Jesus won. Angels will appear in the Passion stories. Mark's angels are here instead. We need to remember these angels for the story Mark tells gets darker and darker until hope has all but vanished. But do not forget at the end of the cosmic battle 'the angels ministered to him'. As we must ever remember that this is 'Good News'.

Jesus ministry in all the Gospels begins when John is arrested. Literally, “Now after John had been handed over” paradidomai will be a key word in the passionstory. Here it is the passive mood. Is this a divine passive, showing that God is behind all that happens? Then Jesus sets out and, while he appears to be like John (Herod Antipas in Galilee will think Jesus is John come back to life [6,6]) he will find his own voice and technique and it will be very different to John's. Later (Chp.6, 1429), we hear of John's execution at the hands of the drunken, boastful Herod. If we were uncertain before, we know now where Jesus' destiny lies.

In an early episode (1,4045) Mark shows what it means 'to bear our sins'. A leper approaches Jesus and asks to be healed. Jesus is 'moved with pity', (though some manuscripts read 'was angry') and heals him. Despite the command to silence the leper speaks out so that “Jesus could no longer go into a town openly, but stayed out in the country; and people came to him from every quarter”. The outcast returns to society; and Jesus is cast out of society, but nevertheless people come to him. The gospel passion story in a nutshell.

In the disputation about fasting we hear, “As long as they have the bridegroom with them they cannot fast. The days will come when the bridegroom is taken away from them, and then they will fast on that day.” (2,19b20). This little incident comes within a larger series of controversies which shows Mark's Literary skill and prepares the attentive listener/ reader for the Passion and cross ahead.

There are five interrelated episodes: the healing of the paralytic who is let down through the roof by his friends (2, 112); the call of Levi and the meal with toll collectors and sinners; in the centre is the controversy over fasting and the wine skins' parable; then the disciples pluck ears of grain to the consternation of the Pharisees; and finally in this group there is the healing in the synagogue of the man with the withered hand. This group has both a concentric structure and an impetus moving the drama forward.

The first and fifth stories concern the healing of a man suffering some form of paralysis and the cures draw negative responses from people in leadership; the second and fourth are controversy stories where eating provokes contention; and the central story also involves eating and dispute but Jesus responds with two powerful images – bridegroom /wedding and garments tearing and wine skins bursting ”Joy at the Messiah's presence is tempered by the violent disruption it will unleash.” [Meier, “A Marginal Jew – Vol IV”, p.269]

The forward movement comes from the increasing enmity and opposition Jesus is facing, pointing towards his passion and death. In the first story an accusation of blasphemy is in the minds of the scribes – the charge Jesus will face from the High Priest (14,64). The Pharisees objections in the second story and loud but directed at the disciples. In the third we hear that the bridegroom (Jesus) will be taken away. The behaviour of the disciples is challenged in the fourth. And the final miracle and the conclusion of this set of five stories sees the Herodians and Pharisees seeking a way to destroy him. WE are only just into Chapter 3!

The first half of Mark's Gospel is a series of teachings and miracles and confrontations. Later in the same chapter 3 the scribes from Jerusalem are saying, “He has Beelzebul, and by the ruler of demons he casts out demons” (3,22)

The Pharisees (='the separated ones') were lay people who sought to live lives of Temple (priestly) purity in their daily living. So each day they would ensure they were ritually clean and upheld all the 663 prescriptions of the law. To be ritually clean involved washings and sprinklings and avoiding contact with anything that could make you unclean, such as a corpse, a sepulchre, or being touched by the great unwashed. Hence they only ate with likeminded Pharisees and ate only what had tithes properly paid on it.=. They accepted an oral Torah, given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai alongside the written Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible(the 'T' of TaNaK). Far from being the miseryguts they are often portrayed or imagined, they were full of joy for the Law, and were considered as models of holiness and righteous by those who wished they could be so themselves but knew they could not be such.

The Herodians were the clients of Herod Antipas, tetrach (ruler of a third viz. a third of the kingdom of his father Herod the Great) of Galilee and an area across the Jordan, not far from where John was baptising. There Herod had a mighty fortress where it is likely John was imprisoned and executed.

The scribes were part of the small group who supported the minority elite. Educated and literate, they were the secretaries to the wealthy.

In the ancient Mediterranean world (and it is not so very different today) the world wideweb was a net work of patrons and clients. A patron gave patronage in the form of gifts, work, financial help to clients who gave their patron acclaim, praise and anything he asked them to do. (Think: Godfather trilogy or any number of Mafia films). The great Patron was the Emperor, all were his clients but some of his clients would be patrons to their clients... And brokers would seek to put patrons and clients together for their mutual benefit, and his own. (The Parables of Mercy talks will develop these details of social science).

By the end of chapter 3, the family of Jesus are out to get hold of him because they think he is mad(3,21). Their intention is to take him prisoner and get him home and keep him there. His behaviour, in their view, is bringing shame on them. (Honour was the great value in this society and shame/ dishonour was to be avoided at all costs. Again, more on this in the Parables of Mercy).

When they get to Jesus and he hears they are there he rejects them. “Who are my mother and my brothers? And looking at those sitting around him, he said, 'Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.'” (3,3334). Family, kinsfolk were the most important social support in the ancient world, Identity, the necessities for living, emotional support came from the extended family. To reject family was effective suicide. Yet Jesus replaces his biological family with a fictive kinship group; a new family of disciples and others. This is truly remarkable. Luke softens the picture, especially regarding Mary whom he portrays at Jesus first disciple, who hears and responds to God's word ”Let it be done to me”.

At the beginning of chapter 6, Jesus returns to his home town where the townsfolk, his kinsfolk, “took offence at him... And he could do no deed of power there, except that he laid his hands on a few sick people and cured them. And he was amazed attheir lack of belief.” (6, 3b.56). Rejected by Pharisees and Herodians, family and kinsfolk, Jesus path of isolation is becoming ever more clear. We then here of John the Baptist's death.

The disciples are consistently given a hard time by Mark. They persistently, almost wilfully, seem to misunderstand. Despite the power of Jesus in word and deed, when he calms the storm they are still questioning, saying to one another 'Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey him?' (4,41). Notice when they return from their missionary journey, Jesus wants to take them away to a quiet place, but he does not praise them, nor see 'Satan fall like lightening' (Lk.10,18). After the feeding of the five thousand Jesus walks on the water, and they clearly have learnt nothing: “And they were utterly astounded, for they did not understand about the loaves, but their hearts were hardened.” (6,5152) After the feeding of the four thousand, Jesus talks of the yeast (=evil) of the Pharisees and they think they are being told off for leaving the sandwiches at home. Jesus is frustrated: “'Do you still not perceive or understand? Are your hearts hardened? Do you have eyes and fail to see? Do you have ears and fail to hear? And do you not remember?'” (8,1718).

In the second half of the Gospel, between Peter's affirmation of Jesus as 'the Christ' and the start of the Passion, Jesus teaches the disciples privately. We can surely be assured that these handpicked individuals will support him to the end? In this section Jesus three times announces his coming suffering and death and on each occasion the disciples, almost wilfully again it seems, are not listening. After the first prediction (8,31) Peter remonstrates with him and it curtly put down. After the second (9,31) the disciples argue about which of them is the greatest. On the third occasion (10,3334) James and John ask to have the seats on his right and left in the kingdom. Several times earlier in the Gospel the disciples' misunderstanding has been underscored, so we should not be surprised by their callous deafness, nor by their later behaviour. Mark is hard on the disciples but these are the ones who will be 'fishers of men' (1,17). The truth Mark is illustrating is that no one van know who Jesus is, nor what hie is about, until we have followed him all the way to the cross. Then his identity and his purpose will be known.

Through the Gospel Jesus is growing more isolated. No one is listening to him, though there are a few people who act as true disciples though they are not among the Twelve – blind Bartimeus who, sight restored, follows Jesus 'on the road'; the woman, anonymous, who anoints Jesus for his burial. As Mark takes us through the Passion story this isolation will grow ever more stark until at the very end Jesus is completely alone.

Jesus is in Jerusalem just a few days prior to his death. After the triumphal entry, he visits the Temple and withdraws. The next day he cleanses the Temple, driving out buyers and sellers and overturning the tables of the moneychangers and the dovesellers. Whatever the meaning of this act (a cleansing? A symbolic destruction?) it is a provocation the authorities are unlikely to ignore. Before an after the description of the Templeevent Mark using that favourite literary technique of inclusion, tells of a figtree cursed and found withered. The purpose of the inclusion is to allow the bread to explain the meat in the sandwich. This strongly suggests that Mark understands Jesus action as symbolically destroying the Temple. Later he will announce, “Do you see these great buildings? Not one stone will be left here upon another; all will be thrown down.” (Mk 13,2).

The next day we hear of three disputes between Jesus and three groups of adversaries: chief priests, the scribes and the elders who question his authority which Jesus rebuffs by asking about John the Baptist (reminding us of his fate); Pharisees and some Herodians who ask about lawful payment of taxes (this same alliance plotted to destroy him in chapter 3); then some Sadducees question him about Resurrection using the story of the seven brothers.

Sadducees were part of the elite and wealthy aristocracy from whose number High Priests were chosen. They accepted only the Torah as authoritative and rejected any notion of oral Law or Resurrection. They disappear after 70CE.

Jesus sees off the opposition but for how long? Between the first encounter and the second and third Jesus tells his final lengthy parable: the parable of the vineyard. This concludes with the son killed. The chief priests, scribes and elders realise the parable is against them and want to arrest him. Only fear of the crowd (at present on Jesus' side) prevent them.

Jesus' final parable concerns a man going on a journey and leaving his slaves in charge and commanding the door keeper to keep watch. “Therefore keep awake for you do not know when the master of the house will come, in the evening, or at midnight, or at cockcrow, or at dawn, or else he might find you asleep when he comes suddenly. And what I say to you I say to all: Keep awake.” (13, 3536).

For whom was Mark writing his Gospel (usually dated in the 70's CE)? Richard Bauckham convincingly argues that each Gospel was written for the universal Church; and we are wrong to limit the Gospel's original audience to the community of the evangelist. The question might better be put: why did Mark write his Gospel? Certainly a factor will have been the deaths of the generation who knew the Lord and a need to preserve the stories and teachings heard from them. But Mark is also writing to encourage a community who have faced or are facing the prospect of persecution for following Christ. Scholarly opinion places Mark's Gospel in Rome where there had been an expulsion of followers of 'Chrestus' under Claudius (49CE) and in the seventies Christians were made the scapegoats by Nero after the great fire of Rome. Other scholarly opinion associates Mark with Syria, and that places theGospel not far from Palestine which had been engulfed by the Jewish Revolt (64 70CE).

One of the reasons for Mark's bleak account is to encourage those who were facing the black and horrible prospect of torture and a slow and agonising death. 'Jesus is there with you' is part of his message. But as we go through the gloomiest Passion account next week, we have to remember that this is “Good News”

Matthew.

I have treated Mark at some length as both Matthew and Luke used Mark as a source. Much of what I've said about Mark applies to Matthew and Luke (hence Synoptic Gospels – view together).

However, both Matthew and Luke open their respective Gospels with an Infancy Narrative which serves, inter alia, to introduce the passion.

After the genealogy Matthew tells the story in narrative form, developing the theme of Jesus as a new Moses. Just as Moses was threaten with death at his birth by a wicked tyrannical ruler so Jesus as an infant is sought by the murderous Herod. The gentile Magi also recall the story of Moses and Balak, king of Moab, and the magus Balaam. The family must flee to Egypt, returning only when the tyrant is dead, and then to Nazareth as his son, Archelaus, is as brutal as his father,

Matthew, like Mark, shows Jesus' destiny in the fate of John the Baptist. But he does not develop the notion of Jesus bearing our sins at the baptism as Mark does. However, Matthew cites the Scriptures frequently showing that Jesus is the fulfilment of Law and Prophets. In chapter 8, after a series of healings Isaiah 53,4 is quoted “he took our infirmities and bore our diseases.” (8,17). And in 12,1721 he quotes at length from Isaiah 42,14: “Here is my servant whom I have chosen... He will proclaim justice to the Gentiles...He will not break a bruised reed or quench a smouldering wick until he brings justice to victory”.

A key theme of Matthew's Gospel is righteousness / justice. Jesus explains his being baptised by John as “Righteousness demands it”. Two of the Beatitudes concern 'righteousness'. (“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled” and “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness' sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” (5, 6.10). Jesus' ministry in word and action is a commitment to justice, demonstrating what such commitment entails and its high price. The cross is the ultimate expression of living for justice.

Matthew adds to the tension as Jesus' final days approach with a fierce denunciation of scribes and Pharisees (chapter 23) which concludes with reference to the shedding of the blood of the righteous and a lament: “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it.! How often have I desired to gather your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! See your house is left to you, desolate. For I tell you, you will not see me again until you say, 'Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord'” (Mt 23, 3739 // Lk 13, 3435).

According to Tom Wright this image of the motherhen is taken from a farm yard setting through which fire is raging. The mother hen gathers her chicks under her wings to protect them from the flames which will certainly kill her. “There are stories of exactly this: after a farm yard fire those cleaning up have found a dead hen, scorched and blackened – with live chicks sheltering under her wings. She has quite literally given her life to save them. It is a vivid and violent image of what Jesus declared he longed to do for Jerusalem and, by implication, for all Israel” . [T Wright, Luke for Everyone” p.171].

Matthew adds a number of parables to Mark's account including the ten wise and foolish handmaidens; the talents, and the sheep and goats all of which end with expulsion of some sort.

Luke.

Luke also provides and Infancy Narrative to open his Gospel in which the birth stories of John the Baptist and Jesus are placed in parallel. Again John's fate points to Jesus' death. Luke does not tell us anything of Herod and his murderous intentions but we are told that Mary “laid him in a manger because there was no place for them in the inn” (2,7); we hear from Simeon that Jesus will be “a sign that will be opposed”(2,34) and we learn of Mary's 'sword of sorrow' (2,35b) which cannot be explained as Mary seeing her son die as Mary is not among the women who see the crucifixion in Luke's account. Mary's Magnificat speaks of raising the lowly, which is at the heart of the Gospelmessage.

At the end of the temptations, we are ominously told that Satan departed “until an opportune time” (Lk 4,13b).

Luke likes overtures (cf Acts 2). And in the scene in Nazara (4,1630) he gives us the entire Gospel in miniature. The quotation from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah (61,12 and 58,6) is Jesus' manifesto; but one which does not include (“a day of vengeance for our God” which may be the cause of the upset of the townsfolk. Jesus care for theoutcasts and marginalised (women especially widows, lepers, foreigners, including hated Samaritans) is highlighted and will be a prominent part of Jesus' ministry and arouse fierce opposition. At the end of the scene Jesus is hustled out of town to a hill top but, miraculously? walks away. I suspect that Luke is telling us that such incidents were not infrequent in the course of Jesus' ministry. His 'words of mercy' will not have gone down well with many people who would prefer to see some 'vengeance from our God'. A parable like that of the Good Samaritan will have enraged many in his audience, as we will see later in the year.

Luke has a strong journeymotif. Jesus 'sets his face to go to Jerusalem” (9,51), the only place appropriate for a prophet to die. Luke also has the lament over Jerusalem and when Jesus arrives at the city the lament is repeated with tears and a prediction of Jerusalem destruction, accurately described postevent, “because you did not recognise the time of your visitation from God (19,44c).

When Jesus has arrived in Jerusalem we hear explicitly the intention to kill him. “The chief priests, the scribes and the leaders of the people kept looking for a way to kill him; but they did not find anything they could do, for all the people were spellbound by what they heard.” (19,47b48).

John.

The picture of Jesus given by John is very different to that painted by the Synoptic writers. Jesus is the Word made flesh( 1,14), but there appears to be more of the Word as God in Jesus than 'one like us in all things but sin'. Jesus is divine “The Word was with God and the Word was God (1,1); “My Lord and my God” (20,28). He has come from God and he will return to God. All that he says and does reveals God. His many “I am” (ego eimi Gk) sayings evoke the name of God given to Moses at the burning bush(Ex 3,14), especially when they are unqualified – Jn 8,58; ... His dying will be his raising up to God; and the means by which his children can return to God. He will face rejection “He was in the world; and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not know him. He came to what was his own; and his own people did not accept him.” (1,1011). But Jesus is always in control. No one has power over him. No one will take his life from him. He will lay down his life and he will take it up again.

After the Prologue the opening scene is an interrogation of John by priests and Levites sent from Jerusalem. This is John's testimony we are told. While we are on the banks of the River Jordan, we are also in a courtroom. John is on the witness stand being crossexamined. This anticipates the courtdrama which brings the storyto its climax.

John, seeing Jesus, declares, “This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world”. Jesus will be condemned at the time (noon) that the lambs sere beginning to be sacrificed in the Temple for the evening celebration. This is then, the Passover Lamb, whose blood brings salvation.

John has Jesus drive the sellers from the Temple in Chapter 2. When asked for a sign to justify his actions Jesus says, “Destroy this Temple and in three days I will raise it up.” . The evangelist interrupts to tell us that he is speaking of the Temple of his body.

The opposition to Jesus is in the open after he cures the simpleton at the Pool of Bethzatha on the Sabbath, a day on which his Father works and so does he. “For this reason the Jews were seeking all the more to kill him, because he was not only breaking the Sabbath, but was calling God his own Father, thereby making himself equal to God.” (5,18).

In chapter 6 there is a crisis in Jesus ministry as many leave him, scandalized by his intolerable language. Peter affirms that he has the words of eternal life and he is the Holy One of God. And Jesus responds by saying that one of the chosen twelve is a devil. Again the evangelist intervenes to tell us he is speaking of Judas Iscariot who, though one of the twelve, would betray him.

In each subsequent chapter we are told that the Jews are looking for an opportunity to kill him (7,1); that there are attempts to arrest him (7,44.45); they take stones and try to kill him (8,59); the man born blind who speaks up for him is thrown out of the synagogue ((9,34); after Jesus speaks of himself as the Model Shepherd there is an attempt to kill him (10, 31) and again accuse him of blasphemy (10,33). Which comes to its climax with the meeting of the Sanhedrin after Lazarus has been raised. Caiaphas declares “You know nothing at all! You do not understand it is better to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.”(11,50)... “So from that day on they planned to put him to death” (11,53).

Chapter 12 opens with Mary of Bethany anointing Jesus “for the day of my burial” (12, 7). After the triumphal entry, Greek seek to see Jesus. This seems to be a signal for Jesus now announces “The hour has come for the Son of Man to be glorified” (12, 23) and speaks of the grain of wheat that must die to bear abundant fruit. Here we have the only note of questioning that we hear from the Johannine Jesus (apart perhaps from the weeping as he prepares to raise Lazarus). “Now my soul is troubled. And what should I say 'Father, save me from this hour? No, it is for this reason that I have come to this hour. Father, glorify your name!” (12,2728a). The question is no sooner asked than dismissed.

John's equivalent of the three predictions of his suffering and death found in all the Synoptic Gospels is characteristically changed to Jesus speaking of being lifted up. The third occurs after this momentary hesitation. “When I am lifted up from the earth I will draw all people to myself” (12,32). The evangelist explains, “He said this to indicate the kind of death he would die” (12,33).

Jesus speaks the first prediction in his conversation with Nicodemus. “No one has ascended into heaven except the one who descended from heaven, the Son of Man. And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” (3, 1315).

The second saying comes in a prolonged dispute in chapter 8. “When you have lifted up the Son of Man, then you will realise that I am (he), and that I do nothing on my own, but I speak these things as the Father instructed me.” (8, 28).

For John Jesus' death is an exaltation. That insight will touch all aspects of his Passionstory.

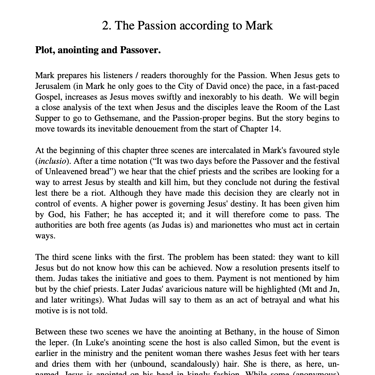

Talk Two

The Passion

According to Mark.

Talk Three

The Passion

According to Matthew

Talk Four

The Passion

According to Luke

Talk Five

The Passion

According to John

Talk Six

Making Sense of The Passion

2015

LENTEN TALKS

BOOK of REVELATIONS (1)

BOOK of REVELATIONS (2)

BOOK of REVELATIONS (3)

BOOK of REVELATIONS (4)

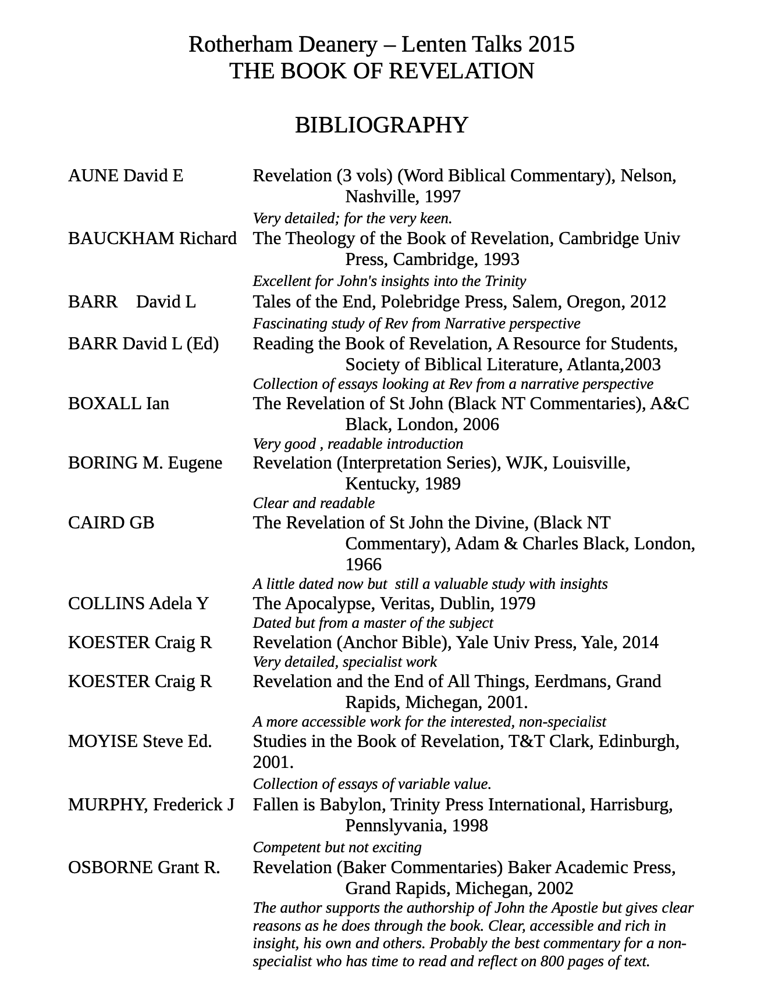

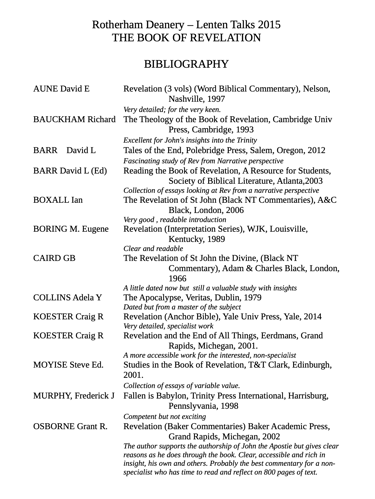

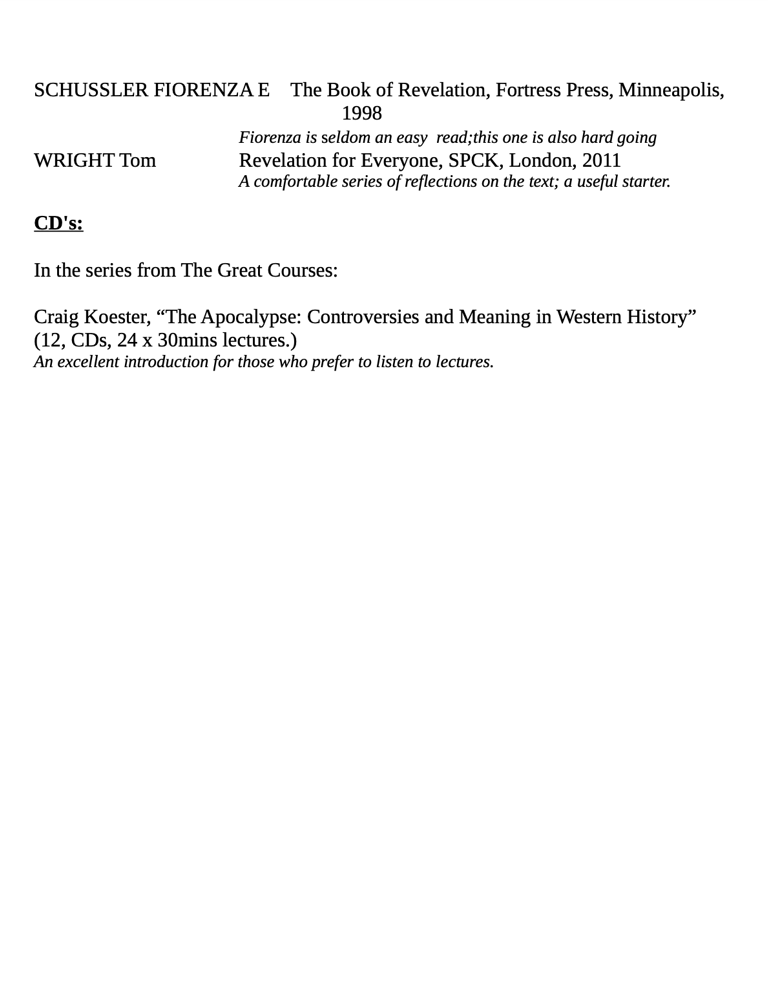

BOOK of REVELATIONS - Bibliography